“My gut tells me underlying motives are at work here that are not being shared!” In the past month, I have heard several variations on this statement in online gatherings. Mistrust has become more prevalent and is giving birth to interpersonal conflict—in a time when we have less personal resilience to cope with it. We need to take greater care when we attribute motives for another’s actions in this precarious season.

What Has Been Taken from Us

A variety of conditions fuel gut-level mistrust in working relationships. A vitriolic political environment, the pandemic, and shifting modes of communication each play a part.

- Loss of shared perspective. The world has become more polarized politically and ideologically. It is hard to find middle ground with others who are not aligned with our personal viewpoints. Lack of shared perspective leads to mistrust and makes it easy to doubt another’s motives.

- Loss of Context. Due to the pandemic, we have lost the casual interactions that support our working relationships. Easy conversations over a shared meal and serendipitous encounters in a hallway no longer happen. We have fewer avenues for learning the backstories that inform motive.

- Loss of Cues. Our communications have become predominantly text-based: emails, text messages, social media exchanges. It is easy to mistake the intent of a message without the vocal inflections and body language that signal joking, anger, exhaustion, or stress. In online meetings, people typically present a flatter affect than they do in in-person gatherings.

You and Your Gut Reaction

In fast-paced, stress-filled environments we often rely on intuition to interpret what is happening. Too often, we put 2 and 2 together to make 5. Rather than waiting for all the facts needed to decide or laboriously reasoning through the facts available to us, we act on intuition.

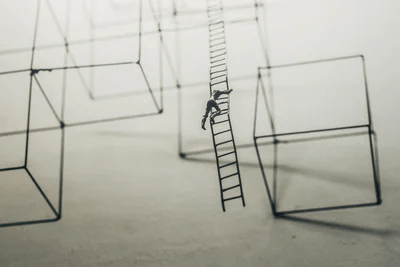

The Ladder of Inference, described by Chris Argyris in 1985, compares intuition to rungs on a mental ladder—each move up the ladder representing a leap of abstraction:

- I experience and observe a situation.

- I select data about the situation that I find relevant, and discard data that feels irrelevant.

- I add meaning to the selected data, based on experience.

- I make assumptions that my data and meaning are accurate and represent some larger reality.

- I use my assumptions to draw conclusions and develop beliefs—promoting what is best for me.

- I act based on my beliefs.

Leaps of abstraction help us to work quickly as we sort out our environment, but they also cause us to ignore facts, skip logical reasoning, and draw inaccurate conclusions.

Testing Your Gut

We can use the Ladder of Inference to slow down our thinking, pay closer attention, avoid unnecessary mistakes in interpretations, and head off interpersonal conflict. Here are five helpful steps:

- Stop! To double-check your gut, you must be willing to call a personal time out, to consider your reasoning and examine your assumptions.

- Identify where you are on the Ladder of Inference. Are you still gathering facts, testing assumptions, interpreting data, drawing conclusions, or deciding what to do?

- From your current rung on the ladder, examine your reasoning by working back down the ladder:

- Why have I chosen this course of action? What other actions have I failed to consider?

- What belief led to the action I chose? Was it well-founded?

- Which assumptions led to my conclusions? Were those assumptions accurate?

- Do I know what he/she/they believe? What are they motivated by?

- What data have I chosen to work with and why? Was I rigorous enough in my analysis of data? Did I have enough data to draw a conclusion?

- What other facts do I need to draw a more informed conclusion?

- Finding a thought partner can help you to test your reasoning and examine your unstated assumptions—but be careful to select a thought partner who does not think “just like you.” To help identify your blind spots, you need someone with a different perspective.

- Make your thinking and reasoning more transparent to others so that they can better understand you. Inquire into the thinking and reasoning of others.

Clarifying Motives Remotely

Much of our communication now is happening asynchronously, meaning that we send a message and then wait for the other’s response. One advantage of working in this delayed way is that it buys us time in between interactions to reflect. We can use these time gaps to work through our inferences before responding.

A long-standing rule of thumb for dealing with misunderstandings is to seek an in-person conversation, because too much can be misunderstood in text communications. In a pandemic, however in-person meetings may not be safe—or distancing and masking may eliminate the benefits.

Online meetings are not always a good alternative. Online meeting platforms invite eye-to-eye engagement that may feel too intense for an emotionally charged conversation.

Consider making use of an older technology—pick up the telephone. You cannot observe body language on the phone, but your listening skills are often heightened when you are not distracted by visual cues. You can notice subtle voice inflections, pauses or nervous reactions that will tell you things your eyes do not see.

Finally, ask yourself, “What would a logical, generous interpretation of this behavior lead me to conclude?” You can err on the side of attributing good intentions to another, and then see where that takes you.

Going through a difficult experience with co-workers can be life transforming. On the other side of the mistrust, a deeper, richer relationship may be waiting to emerge.

Susan Beaumont is a coach, educator, and consultant who has worked with hundreds of faith communities across the United States and Canada. Susan is known for working at the intersection of organizational health and spiritual vitality. She specializes in large church dynamics, staff team health, board development, and leadership during seasons of transition.

With both an M.B.A. and an M.Div., Susan blends business acumen with spiritual practice. She moves naturally between decision-making and discernment, connecting the soul of the leader with the soul of the institution. You can read more about her ministry at susanbeaumont.com.