Many of the pastors, priests and rabbis with whom I interact are working harder than ever—as are the support staff and volunteers who are serving with them. In many congregations, new programs are emerging while existing programs are being refined and facilities upgraded. Yet participation and pledge rates are at best stable or declining in the great majority of U.S. congregations. Despite all the hard work, why are so many congregations declining?

The reasons for this decline include macro trends such as demographic changes, the ongoing technology revolution, and visible leadership crises that have impacted multiple traditions. But one overarching reason may be that congregations (like many other organizational sectors) are still operating on Newtonian principles in a social universe that no longer functions that way.

The old world

In the natural sciences, Newtonian physics assumed a stable, mechanistic world in which observable effects could be linked back to their causes in a predictable and linear way. In the social sciences, Newtonian principles assumed stable organizational environments and dictated centralized command and control structures and fixed planning cycles. Most of our congregations (and virtually all of our denominational and judicatory structures) emerged in a social context dominated by these Newtonian assumptions.

The reality, of course, is that we no longer live in a Newtonian universe (if we ever did).

Chaos Theory and its twin, Complexity Theory, emerged in recent decades in the natural sciences—particularly biology, chemistry and physics—to explain the universe (at both macro and micro levels) that scientists are actually observing. As Ian Stewart summarizes paradoxically in Does God Play Dice? The New Mathematics of Chaos: “Chaos theory tells us that simple systems can exhibit complex behavior; complexity theory tells us that complex systems can exhibit simple ‘emergent’ behavior.”

Pattern out of chaos

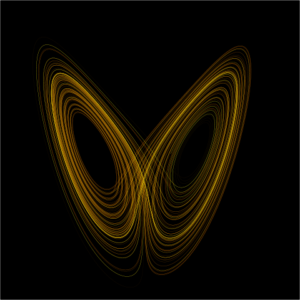

Rather than a linear, stable, and fixed universe, natural scientists now describe multiple non-linear, organic, and adaptive subsystems and systems that may appear chaotic but in fact operate in self-organizing ways that produce patterned behaviors. In Leadership and the New Science, Margaret Wheatley applies what natural scientists have learned about chaos and complexity to organizational and leadership realities. Three clear implications emerge for leaders attempting to navigate these post-Newtonian realities, as follows:

- Within any system, it really is all about relationships. Wheatley provides insights from quantum physics (the sub-atomic level), noting that “in the quantum world, relationship is the determiner of everything. Subatomic particles come into form and are observed only as they are in relationship to something else (p. 11).” Likewise in congregations, the quality of relationships in the system will be the primary determinant of virtually all outcomes—and particularly of a leader’s effectiveness. Wheatley proposes that this understanding of relationships turns traditional definitions of “power” on their head, as “power in organizations is the capacity generated by relationships (p. 39).”This principle (that it’s all about relationships) has prompted many congregational leaders to focus less on telling others what to do (and believe) and more on sharing and inviting stories. Such “narrative leadership” has been modeled by many great spiritual leaders (including Moses, Jesus, and Mohammad), and is increasingly being studied and implemented by contemporary religious leaders. While dogma tends to divide, stories connect. (The book Finding Our Story: Narrative Leadership and Congregational Change by Larry Golemon explores this leadership modality in more detail.)

- Where there is shared meaning, we can trust people to self-organize. In the natural world, multiple “invisible fields” (such as gravity) shape behavior and place natural limits on the animals and plants that live within these fields. In organizations, Wheatley proposes, clear vision and value statements and a shared culture also operate as “invisible fields.” In the presence of clear and shared meaning, congregational members and employees don’t have to be “told” what to do…they will know what to do. As Wheatley says, “Systems achieve order from clear centers rather than from imposed constraints (p. 132).”This principle (of the power of invisible fields) has prompted many congregations to move away from the “command and control” model implicit in board and committee structures to the “communicate and coordinate” model required by self-organizing teams. Cultural adjustments are required to make such a shift, and most congregations that have moved to “team ministry” still retain a slimmed-down board and committee structure. But the biggest hurdle to overcome is often the willingness of formal leaders to trust that teams will truly self-organize—and allow them to do so.

- “Adaptive Leadership” trumps “Strategic Leadership.” In a Newtonian universe (a stable environment), change is both predictable and manageable. In a Newtonian organizational universe, planned change is normally initiated by top organizational leaders in three to five year “strategic planning cycles”—ideally accompanied by specific action plans and indicators to measure goal achievement. Such planning is often done in an effort to position the organization for a stable future in the midst of a changing environment. But chaos theory “has led to a new appreciation of the relationship between order and chaos.” Rather than view chaos as destructive and undesirable, natural scientists have concluded that “chaos is necessary to new creative ordering” (Wheatley, p. 13).

In congregational life, effective leaders will continue to “lead strategically” and will not abandon strategic planning as an opportunity to revisit Mission, Vision and Values and to think creatively about core priorities. But many will also adopt the core leadership principle implicit in chaos and complexity theories—that in the midst of rapidly changing environments the most appropriate leadership modality is “adaptive leadership.” What is adaptive leadership? It’s leading the process of helping a group or organization to take what Glenda Eoyang calls the “next wise action”—the step that is needed in a changing environment where time and information are both limited resources.

Most congregational leaders have long known that they don’t operate in a Newtonian universe where systems are static and change processes are linear. But now organizational theorists and researchers are discovering that much of what we are learning about natural systems also applies to our socially constructed ones. Leaders who focus on shared meaning and relationships and learn how to practice adaptive leadership will be the ones best positioned to help their congregations thrive in a world of chaos and complexity.

David Brubaker has consulted with organizations and congregations in the U.S. and a dozen other countries on organizational development and conflict transformation. He is the author of Promise and Peril, on managing change and conflict in congregations, and When the Center Does Not Hold, on leading in an age of polarization. David serves as Dean of the School of Social Sciences and Professions at Eastern Mennonite University and is a professor of organizational studies.